Luck, Shooting Percentages, and the Boston Pride

Reflecting on luck in the sport of hockey

We don’t discuss luck very often in women’s hockey. Instead, we tend to focus on skill, tactics, and more mysterious variables like chemistry and heart. Understandably, we don’t like to think that luck holds too much sway over the outcome of games but sometimes the best explanation — at least at the surface level — is the difference between being lucky and unlucky. After all, the game is played with a frozen rubber disk on a sheet of ice. Sometimes, you run into a hot goalie. Sometimes, the puck just doesn’t bounce your way.

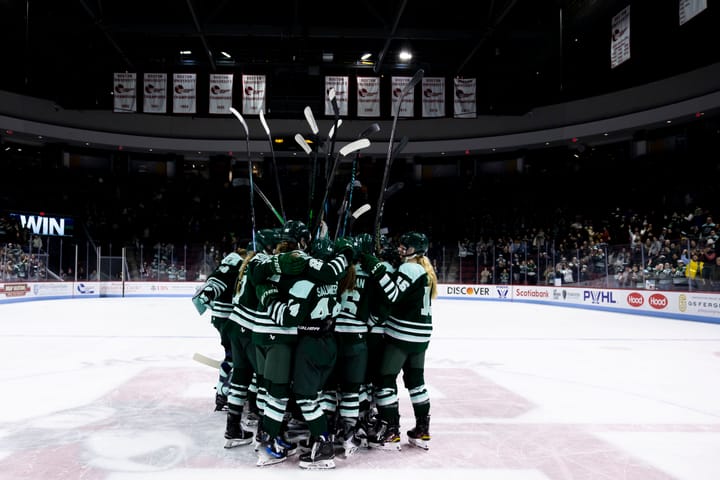

Last year, the PHF’s Boston Pride were a preposterously unlucky hockey team — right up until the playoffs. As you probably remember, the Pride won the 2022 Isobel Cup. So, it can be easy to forget just how unlucky they were in the regular season.

So, what does unlucky look like?

In 2021-22, Boston had a team shooting percentage of 6.92% in 20 games — when we take the Pride’s two empty-net goals out of the equation, that percentage crashes down to 6.64. That number might not immediately register as being remarkable so let’s look at it from a different perspective. Opposing goalies (and therefore opposing teams) had an average save percentage of .933 against the Pride last season. For context, the league average Sv% in 2021-22 was .913 and the league average at the 2022-23 holiday break is .907.

More or less, that’s like having to play against Amanda Leveille — who had a .937 Sv% in 2021-22 — when she’s on top of her game. Every. Single. Game.

That 6.92 Team Sh% is why a team that would go on to win the Isobel Cup averaged just 2.4 GF/GP and had an abysmal 5.92 PP%. The last time Boston had played a full season (2019-20) they averaged 4.96 GF/GP and had a 22.86 PP% (in a 24-game season). That’s half as many goals, on average, per game. The difference between those two numbers is wild, especially when you consider how much overlap there was between the two rosters: Jillian Dempsey, Kaleigh Fratkin, McKenna Brand, Christina Putigna, Mallory Souliotis, Tori Sullivan, Mary Parker, Lauren Kelly, and Jenna Rheault.

As I mentioned earlier, team shooting percentage is surface-level analysis, but it’s pretty much the best we can do with the data that’s publicly available. If Boston took fewer shots from high-danger areas at evens and on the PP it would drag down the team’s shooting percentage. But we don’t have public shot quality data or metrics like xGF% in women’s hockey. With that said, we can look at something like team shooting percentage as a place to start digging when we try to understand why a team as good as the 2021-22 Pride went 10-5-5 before the playoffs.

Even without better public data, we know that a 6.92 Team Sh% is dreadfully unlucky. It’s stepping on every crack of every sidewalk in town unlucky. It’s walking under the biggest ladder in the world unlucky. That hard luck in shot success represented itself in Boston losing 7 games by a one-goal margin, including a stretch of 5 straight losses by a single goal. On those nights, it didn’t matter that Katie Burt was having a historically sensational season — Boston just couldn’t score enough goals. On some nights, it felt like they couldn’t buy a goal.

The good news for the Pride is that through 9 games of the 2022-23 regular season, that curse appears long gone — likely exorcised in utter euphoria with an Isobel Cup celebration. This year’s Pride are shooting at 10.48% while averaging nearly the same volume of shots they had last regular season. You can’t make this stuff up.

2021-22 Pride

Team Sh%: 6.92

Team PP%: 5.92 (4 GF)

SF/GP: 34.70

2022-23 Pride

Team Sh%: 10.48

Team PP%: 17.2 (6 GF)

SF/GP: 35.00

I think about the Pride’s 2021-22 season a lot. Why? Because it was so statistically preposterous for a team that talented to struggle so much to score, especially on the power play. I also think about it as someone fascinated by sports psychology who witnessed an entire team change its demeanor after embracing what has become a governing law of the universe for every Pride fan: ‘Keep Calm and Trust Jillian Dempsey’. And I know I will always think about it whenever I am mulling over luck in the sport of hockey.

Boston Pride head coach Paul Mara wearing a "Keep calm and trust Jillian Dempsey" hoodie in the PHF media availability.

— Mike Murphy (@DigDeepBSB) March 22, 2022

We sometimes hear players and coaches talk about earning lucky bounces with a good work ethic and by playing the right way. Maybe that’s why our sport has so much superstition and ritual. In truth, a change in fortune can elude a team for weeks, if not months. It’s wild to consider that sometimes all the film study, practice, and preparation in the world can be spoiled because a frozen disk of rubber just isn’t bouncing your way. Or maybe all that matters is that you think it isn’t bouncing your way.

Maybe you’re gripping your stick too tight because you haven’t scored in a few games, maybe you can’t help but put the puck right into the logo on a goalie’s chest, or maybe you missed that last open shot so you elect to pass when you absolutely shouldn’t. Hockey can do that, even to the best players in the world.

It might sound silly, but I find it comforting that Boston is off to a strong 7-2-0 start this season. Why? Because it makes sense. I look at that roster and how that team plays and I think they should be winning hockey games. That’s why I look at the Connecticut Whale’s current 7.48 Team Sh% and feel confident that it won’t last. Well, maybe I should say I feel confident that it shouldn’t last.

It is comforting to know that a team as great as the 2021-22 Pride eventually overcame their hard luck even though it came right down to the wire. Appropriately, Boston played their best hockey when it mattered most and won the games that mattered most. Something changed. The power play that failed so often in the regular season scored 6 times in 9 opportunities in the playoffs. The same team that shot 6.92% in 20 GP shot 15.95% in 3 postseason games. Good luck, bad luck, leadership, confidence, sample sizes — whatever you want to call it, make sure to also call it hockey.

And hockey is great.

The data used in this story was tracked and collated by the author and can be found at TheirHockeyCounts.com.

Comments ()